Reel Breakdown #34: ROSEMARY'S BABY (1968) ~ Modern Horror Still Can't Escape This Film's Shadow

The Movie That Turned Safe Spaces Into Silent Traps

Roman Polanski's Rosemary's Baby (1968) didn't just change horror — it transformed it into something more personal, terrifying, and claustrophobic than anything audiences had seen before.

Rosemary's Baby took a distinct route, diverging from the typical monster-from-the-swamp flick or slasher. It didn't rely on jump scares or bloodbaths, but rather on a more psychological and subtle form of terror, a unique approach that intrigues and fascinates the audience.

This was psychological terrorism masked as everyday life, where the enemy isn't some creature in the woods — it's your neighbor, your husband, the walls closing in around you.

Polanski, who had already stunned the international scene with Knife in the Water (1962) and Repulsion (1965), directed Rosemary's Baby with the precision of a man setting a carefully wound trap.

And it was his first American film — a central career pivot that should've solidified him as one of Hollywood's premier directors.

Instead, what followed is the tragic collision of art and artist: the Sharon Tate murders, a series of brutal killings that shocked the world and involved Polanski's wife, and, years afterward, Polanski's notorious legal issues, controversies that have rightly complicated any conversation about his legacy.

But let's get something straight: talent and personal demons often go hand-in-hand. Caravaggio painted saints while murdering in the streets. Hemingway wrote poetry between blackouts.

Polanski's life outside the frame is a mess; inside it, he is a master.

And Rosemary's Baby is perhaps his purest act of filmmaking brilliance.

Let’s break it down.

Claustrophobia and Paranoia as Art Form

The greatest trick Rosemary's Baby pulls is that it never overplays its hand.

Polanski makes the terror so mundane that it festers under your skin.

The Dakota (rebranded as the "Bramford" in the film) — a real, massive, Gothic New York apartment complex — becomes a prison, a maze of paranoia.

Cinematographer William A. Fraker (Bullitt (1968), Heaven Can Wait (1978) shot on 35mm Eastman Color film stock using Panavision cameras, and you can feel the difference.

The film has a slight graininess and a subdued, pastel-colored palette that never stands out too much. It makes it feel sickly, perfect for a story about a woman who doesn't realize she's being poisoned spiritually and physically.

The aspect ratio? 1.85:1 — a wide enough frame to feel real but still boxy enough to trap Rosemary inside every scene.

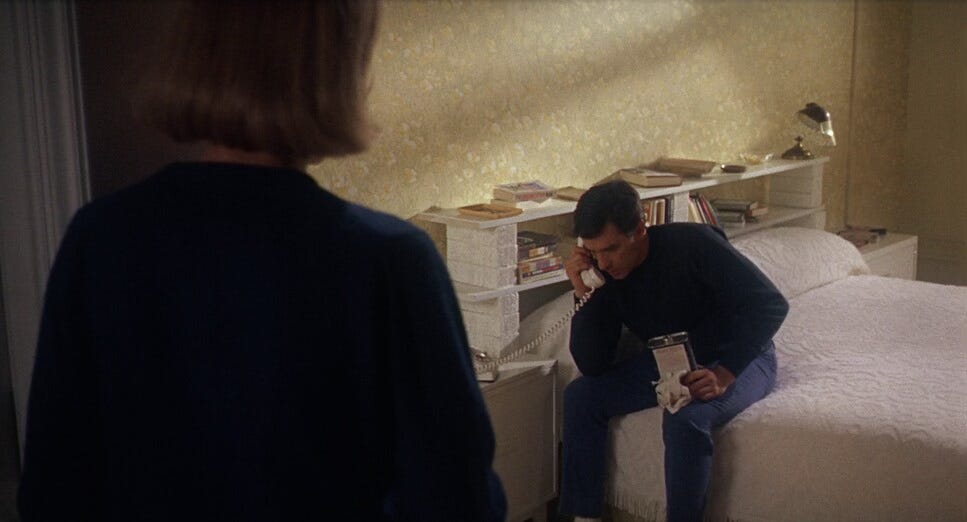

Look closely: Polanski often frames action from doorways, hallways, and partial views, making you lean forward and squint, like you're eavesdropping — complicit in her surveillance.

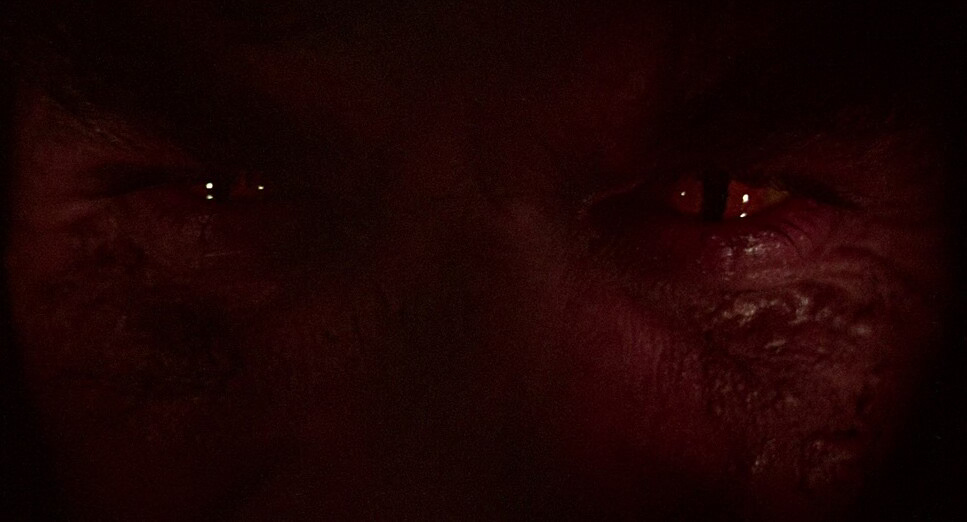

The dream sequences are a masterclass.

Shot with handheld looseness and a mix of practical effects, religious imagery, and sexual violation, it feels like slipping underwater: you know it's wrong, but you can't wake up.

The sound design is huge here — normal noises blend into demonic murmurs.

Polanski's direction here is nearly invisible: no overt "dream" filters or dissolves.

He trusts the audience's subconscious to think something is wrong.

The 1960s Were Already a Nightmare

Released in June 1968 — just two days after Robert Kennedy's assassination and during a year drenched in political assassinations, protests, and violence — Rosemary's Baby felt like an eerie mirror to America's collective dread, tapping into the societal anxieties of the time and amplifying them through the lens of horror, making the audience feel connected and understood.

The 1960s weren't all peace and love; they were marked by betrayal, secrecy, and the collapse of old institutions.

Rosemary's Baby weaponized that anxiety and domesticized it:

The idea is that the people you trust most—your spouse, neighbors, doctors—conspire against you.

Ira Levin's 1967 novel was a bestseller. (Yes, that fast — they optioned the book almost immediately.) Still, Polanski stripped it of overt horror and leaned into something colder: reality distorted only slightly but fatally.

Selling Your Soul, Piece by Piece

If you're looking for the devil in this movie, don't look for horns.

Look at Guy Woodhouse (John Cassavetes, brilliant in his slimy nonchalance).

The guy isn't possessed.

The guy isn't cursed.

The guy is just...ambitious.

He sells his wife's body for a few acting gigs and better lines in a play.

In Rosemary's Baby, the real evil isn't black masses and devil spawn.

It's careerism.

It's American ambition.

It's the willingness to barter morality for personal advancement — a Faustian bargain with no demons needed, just talent agents and handshakes.

The character arc is beautifully horrific:

Rosemary goes from trusting innocence to isolated, gaslit hysteria, but doesn't "snap" into a traditional horror scream queen.

She fights, reasons, and struggles, even when drugged and betrayed.

When she finally sees her demon child — the moment the whole film builds toward — she doesn't destroy him.

She cradles him.

Because it's hers.

Blood trumps fear.

Love is irrational.

And that ambiguity leaves you cold long after the credits roll.

The Birth of Prestige Horror

Without Rosemary's Baby, you don't get:

Hereditary (2018)

The Witch (2015)

Get Out (2017)

Even Kubrick's The Shining (1980) learned from Polanski's use of vast spaces and tight corners to induce dread.

Polanski's meticulous control over sound, space, and character perspective is now the blueprint for every "elevated horror" film you pretend you aren't too scared to finish.

Final Take

Evil doesn't need a jump scare.

Evil needs you not to ask questions.

Rosemary's Baby is more than just a horror movie.

It's a diagnosis of our most fundamental fear:

That the people closest to us aren't protecting us — they're offering us up.

And that's why, even fifty-five years later, it still crawls under your skin.