Reel Breakdown #14: THE GRADUATE (1967) ~ This Film Predicted Your Quarter-Life Crisis… And No One Talks About It

How a Silent, Sweaty Dustin Hoffman Captured the Chaos of Not Knowing Who You Are

The Graduate is one of those films people love to over-intellectualize, as if it were some museum piece.

But if you strip away the praise, the Criterion label, the Simon & Garfunkel nostalgia, you’ve got a kid who doesn’t know who the hell he is, surrounded by people who pretend they do.

And that’s what makes it brilliant. It’s not here to impress you. It’s here to make you uncomfortable.

Mike Nichols didn’t direct this like a filmmaker trying to prove something. He directed it like a guy who already knew everything was broken.

And instead of fixing it, he zoomed in on the cracks. The film doesn’t talk to you—it stares at you.

Long silences.

Glass between people.

Shots that don’t cut when they’re supposed to.

Everything is uncomfortable, and that’s the point. This discomfort in the visual storytelling keeps you on the edge of your seat, eager to see what unfolds next.

Let’s break it down.

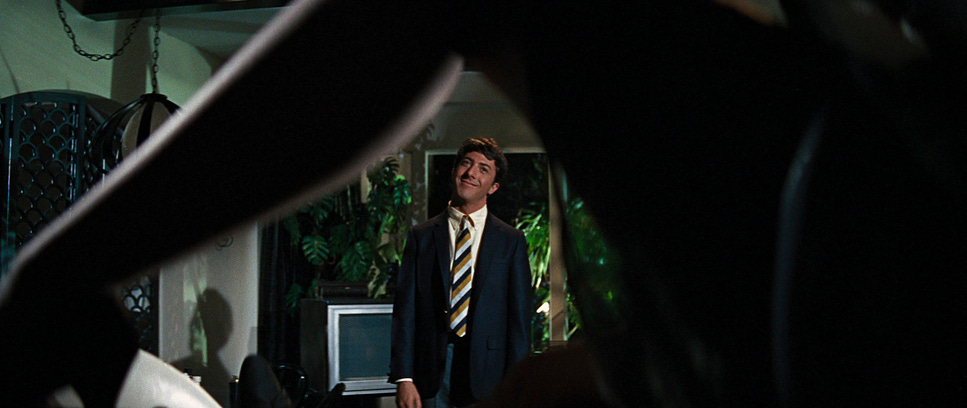

The Camera’s Not Your Friend. It’s a Confessional Booth.

Right out of the gate, Dustin Hoffman’s Benjamin is on a literal airport conveyor belt—moving, not walking, just being transported. And not forward—but left, visually implying regression.

That’s how Nichols introduces us to his protagonist: not with purpose but with drift.

Everything in this film tells you something, even if it’s pretending not to. Look at how Surtees shoots rooms. Lines everywhere. Hallways, blinds, bedposts, doorframes. Characters are boxed in, framed like exhibits at a zoo.

And Benjamin?

Always off-center.

Always swallowed by space or crushed by angles.

He’s not in control.

He’s a product—delivered home in a suit, gift-wrapped for a future he doesn’t want.

Line, Shape, and Control—A Visual Power Struggle

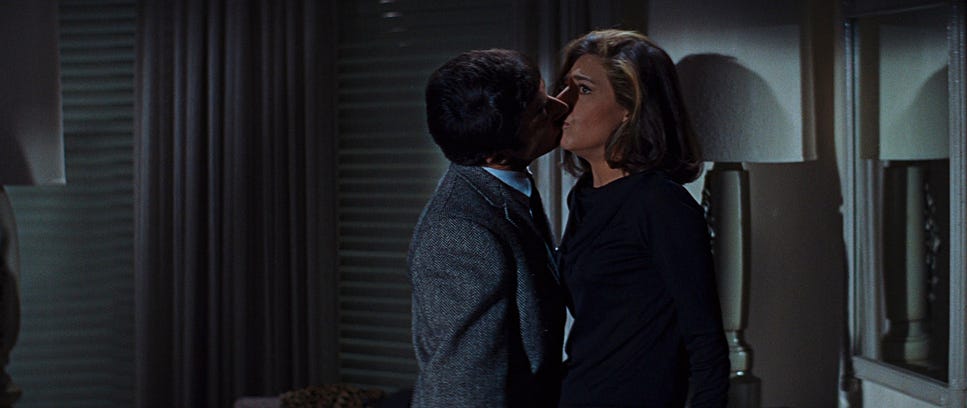

Let’s talk about that infamous seduction scene. Mrs. Robinson is in control from the first glance. She owns the space, owns the silence, owns the frame.

Benjamin blurs behind her like an afterthought when she stands in the foreground.

He’s a guest star in his breakdown.

The furniture, the architecture, even the shadows—all sharp, angular, aggressive. It’s like the house is judging him, too.

And it should.

He’s not a rebel.

He’s a passenger.

That’s the beauty of Nichols’ direction. He’s not showing you what’s happening—he’s letting it trap you. And when Benjamin finally starts making choices, they’re loud, messy, and impulsive. You get the feeling he’s trying to burn down the house to see what’s underneath.

The Script Doesn’t Waste Time—It Wastes Lives

Buck Henry’s script is simple but deadly. Dialogue isn’t about communication—it's about miscommunication.

Everyone talks past each other.

Parents ask what Benjamin will do with his future as if they’re ordering takeout.

Mrs. Robinson doesn’t want love; she wants distraction.

Elaine is supposed to be the “solution,” but she doesn’t know what she wants until it’s too late. The script's emphasis on miscommunication will make you feel the characters' frustration and confusion, drawing you deeper into the story.

And it doesn't feel heroic when Benjamin finally “takes action,” running into a wedding and hammering on the Glass like a man who has watched too many movies about grand romantic gestures.

It feels desperate.

That final bus scene?

That blank stare?

It’s not a victory.

It’s aftermath.

This stress on the aftermath of Benjamin's actions will make you feel the weight of his decisions, leaving a lasting impression long after the film ends.

What nobody tells you about doing what you want instead of what everyone else wants is that you still don’t know if it’s the right thing. You know it’s yours.

Themes You Feel in Your Spine, Not Your Brain

This isn’t a love story. This isn’t even a story about rebellion. This is about what happens when you realize the people giving you advice are just as lost as you are.

It’s about sex as an escape, love as an accident, and adulthood as a trap disguised as a plan.

Is the idea that graduating into adulthood some win? Nichols laughs at it. He gives you a protagonist who “has it all”—education, looks, money, opportunity—and makes it feel like a prison sentence.

What the Film Schools Won’t Teach You

Most breakdowns will talk about how this film broke the rules and redefined cinema. Sure. But forget that. What matters is that the graduate holds a mirror to that sinking feeling in your gut when you realize life isn’t waiting for you—it’s already happening.

It’s not about Benjamin.

It’s about you.

So yeah—maybe this film is dated. Perhaps it’s too quiet for modern audiences. But its message?

Timeless.

Because there’s still a generation out there staring blankly out a bus window, wondering:

“Now what?”