I’ve been lucky to visit Okinawa in my early 20s.

Let me tell you—Japanese culture is something else. If you get the chance, go. But we’re here to talk about film. I got my introduction to the heavy hitters of Japanese cinema—Kurosawa and Mizoguchi—and wrote some essays and learned about Ozu. But I never really dug into his work.

That changed recently during a cinematography lecture where my professor casually mentioned a legendary Japanese director who exclusively shot with a 50mm lens. The dude never took suggestions from DPs.

Just straight-up ignored them. I thought, Okay, that’s hardcore. But I forgot to ask who it was.

Naturally, I did what any normal person with an ounce of curiosity would do: I Googled a Japanese director who only shot with a 50mm lens.Boom—Yasujirō Ozu.

So, I figured, Alright, let’s see what this 50mm-only style looks like. I threw on Late Spring (1948), and guess what?

That 50mm is fucking gorgeous.

Let’s break it down.

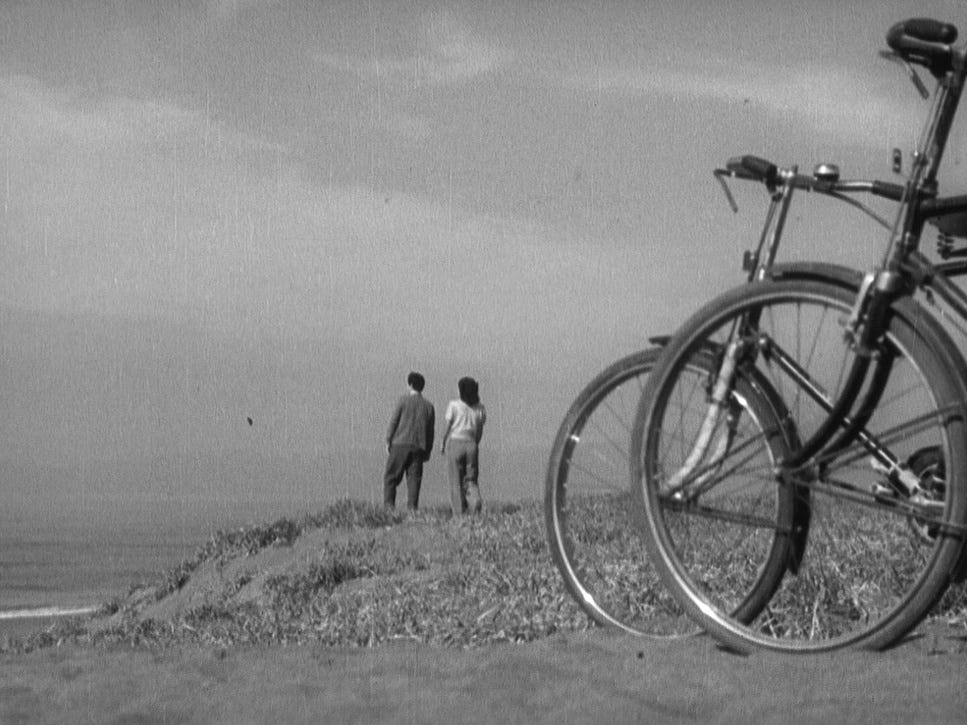

Ozu’s approach to shooting is unlike anything else. Instead of relying on fancy transitions, unnecessary dissolves, or bullshit stylistic fluff, he fills in the gaps with stunning cinematography. But it’s not just about capturing a setting; he transports you to 1940s Japan. The problems, the concerns, the entire atmosphere—it’s palpable. And that 50mm lens? Absolute perfection for capturing depth—foreground, background, objects, people—all in one beautifully balanced frame.

Then there’s his signature low-angle “tatami shot”; let me tell you, it’s a game-changer. It creates these breathtaking vanishing points, making his compositions ridiculously pleasing. The set design and blocking? Meticulously crafted. Every frame is a painting.

Another thing is Ozu’s use of linear motifs in his transitions. Train tracks, telephone wires, signage, and the lines in traditional Japanese homes—vertical, horizontal, intersecting—are all deliberate. It’s wild how underrated his cinematography was, probably in post-WWII America, where film language was heading in a completely different direction.

Most directors default to over-the-shoulder shots during dialogue. Not Ozu. He throws you right in the middle of the conversation, breaking the conventional 180-degree rule and placing you face-to-face with the characters. It’s an intimate, almost intrusive feeling—like you’re sitting with them rather than watching from the sidelines.

This is why Ozu is quickly becoming one of my favorite directors. His work is deceptively simple but deeply profound.

I’m diving into the remaining two films of his so-called Noriko Trilogy—Early Summer (1951) and Tokyo Story (1953)—so expect more on this soon. Stay tuned.

By Chris Branch

Images sourced from: ShotDeck. https://shotdeck.com/browse.